Learning from the Global South: strategic public space design for the informal city

Published 5 October, 2022

‘Critical urbanities – Fragmented Cities and Water Landscapes’ is a Linnaeus Palme Partnership between SLU and the University in Buenos Aires (UBA). In this context, landscape architecture scholar Caroline Dahl of SLU Landscape travelled to Buenos Aires in May 2022 for a teacher’s exchange and engaged in a conversation with urban researcher Max Rohm of UBA’s Architecture and Urban Design Faculty.

Caroline Dahl and Max Rohm call for the acceptance of informal settlements as part of today’s urban realities and suggest including strategic spatial design in urban transformation research and teaching as practised in Living Labs. This resonates with SLU Urban Futures’ commitment to offer a critical perspective, beyond Northern vantage points, regarding questions of urban sustainability.

A taxonomy of urban evolution

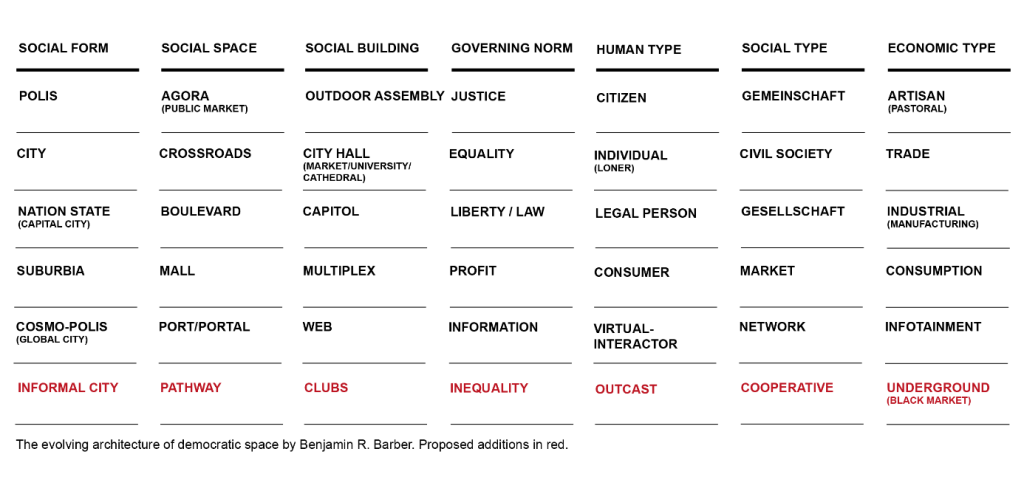

The American political theorist Benjamin R. Barber wrote a text back in the early 2000s that resurfaced in my mind when I recently talked with Max Rohm, Argentinian architect and professor at the University of Buenos Aires. Barber, primarily known for his work on participatory democracy, wrote the epilogue entitled The City as Democracy’s Forge for the anthology Out of Ground Zero: Case studies in Urban Reinvention, published in 2002. In this essay, Barber develops a taxonomy to discuss architecture as a tool for driving democratic space.

Within a gradient that varies between levels of independence and interdependence, Barber describes the evolution of the urban, from Polis to City to Nation-State, eventually concluding with more contemporary social forms such as Suburbia and the Global City. His taxonomy also defines categorisations of social space, social buildings, governing norms, human type, social type and economic type. Other well-known concepts that appear in this taxonomy are Tönnies’s Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft, as well as spatial elements such as the agora, the crossroad, the boulevard and the mall.

The absence of the informal city

Looking back at the essay twenty years later, it is a surprise to me that the informal city is not mentioned in the text, nor in part of the taxonomy. According to the World Bank, around 30% of the world’s urban population currently lives in informal settlements, residential areas where inhabitants endure a lack of services like electricity, sewage and potable water; have no tenure of land or dwelling; and withstand inadequate sanitary conditions. How can we better understand the constraints of the informal city in general and how is public space produced and sustained in such areas? Max Rohm, together with fellow researchers and students from the University of Buenos Aires and other institutions, have first-hand experience of these places, specifically in relation to the effects that the introduction of public space can have in precarious urban situations.

Through a transdisciplinary research project that entailed a 5-year long process, public space was constructed in Villa Tranquila, an informal settlement in Avellaneda, a borough in the south-eastern part of Buenos Aires along the Riachuelo river. The formation of these settlements started with the migrations to large cities from rural towns that emptied out due to a lack of work as an effect of technical improvements in agriculture after the Second World War. However, when people moved to these cities, they could not afford to buy a home, and no formal social housing options existed at the time. As a result, they took the matter into their own hands and started to build their homes on underused state- and privately-owned land. The situation worsened over the years in parallel with an unstable Argentinian economy and the country’s periodic economic crises. Today, 20% of the inhabitants of the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires live in informal settlements. Max Rohm tells me that in 2003/2004 the Municipality of Avellaneda started to develop an urbanisation plan, concentrating on the construction of housing and the development of strategies for water management at the site.

The role of public space

When asked about the absence of a public space strategy in the urbanisation plan, Max Rohm explains that public space is not considered an utmost necessity by the inhabitants of the settlement or the Municipality – unlike a roof over your head or basic accessibility to water, electricity, and public transport. In addition, housing produces real estate value, which is ancillary to the intention of the government to annex those areas to the formal governance of the city.

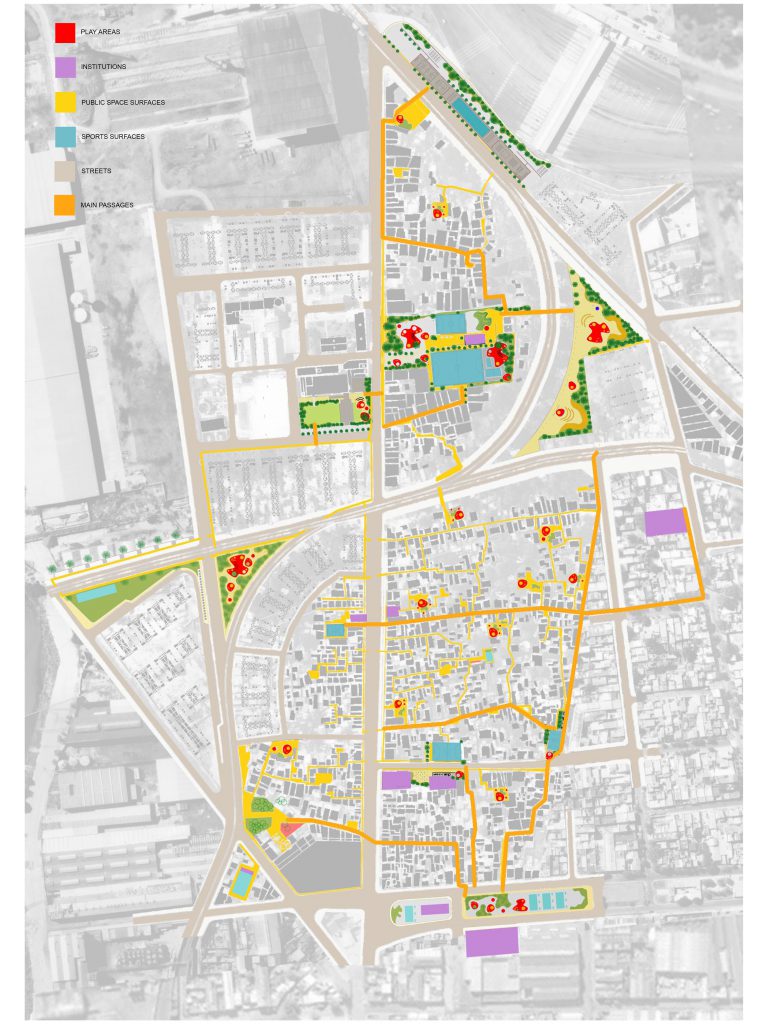

Apparent to the research team was that the Municipality had relatively poor knowledge of the area regarding local cultures and what places were valued by the inhabitants. As a response to this knowledge gap, a mapping was initiated with a group of local and international students. According to Max Rohm, the settlement’s neighbours responded very positively to the surveys and interviews carried out by the team, and it was surprising to see how open-hearted the inhabitants were to those students. From the various conversations, it was concluded that public space in Villa Tranquila should be articulated as a network of vacant lots situated along important everyday circulation routes, adjacent to pre-existing cultural or commercial structures, with a programmatic emphasis on play, sports and rest spaces for the elderly. One of those new public spaces, Vicente Lopez Plaza, was built through a collaborative process with the community, entailing the definition of programme, location and design, as well as the construction of the space.

Based on the experiences in Villa Tranquila, I asked what value public space has acquired in the area. Max Rohm argued that on an everyday level the inhabitants have experienced a contextually rare opportunity to find a place of peace in their neighbourhood, where children become protagonists of urban improvement as their play activities act as catalysts of communal ties. On another level, the project has offered inhabitants an experience in which they become entitled to something that is usually only part of the formal city – public space – and a chance to understand the possibilities and potential of such spaces. In this sense, public space represents the right to the city every citizen should be entitled. It is doubly functional: as a play, sports and leisure area, and also as the spatial manifestation of citizens’ rights. Everyone should be aware of their urban rights, regardless of whether they are an inhabitant of the formal or informal city, Max Rohm says.

Integration as a process

Understanding informality as an inseparable part of the contemporary city is something Max Rohm returns to during our conversation. In his work, he talks about two different concepts in relation to the management of informal settlements: formalisation and deinformalisation. He explains that formalisation has been the ‘old school’ approach for local governments to deal with informal settlements, usually implying the eradication through demolition and relocation of inhabitants to pursue a ‘normalisation’ of the city as informal settlements have historically been seen as negative and bothersome, as something abnormal.

On the other hand, to use the term deinformalisation is to presume that there should be a process where the informal city metamorphoses into a formal city through incremental changes over time. Recognising the present sheer expanse of informal settlements in cities globally, gradual change makes transformation possible, mainly because it is not disruptive for the millions of people living in these areas. Informality is an urban phenomenon that cannot be seen as abnormal in the contemporary metropolis any longer and must be taken as part of its expansion process, as a substantial tactic of urban growth.

The contemporary idea of public space was born in the modern 20th-century city, becoming an imperative to its inhabitants as the main spatial representative of the right to the city. Max Rohm claims that the question of allowing informal settlements to become part of urbanity is also related to this fact: if we understand informality as an undeniable phenomenon of urban growth, public space as an intrinsic social necessity could be the answer to trigger processes of integration. Hence, despite informal settlements being a transient stage of modern city development, it is urgent that they become better places for habitation during their typically decades-long deinformalisation process.

A six-step methodology for the integration of informal settlements in the formal city through public space creation was developed as part of the research project in Villa Tranquila. The aim of the methodology is to be generalisable enough to be relevant in similar contexts around the world:

Step 1: Select an appropriate site and get to know the site and the municipal government to enable the eventual formalisation of the new public space.

Step 2: Interact with neighbours and other parties related to the settlement to generate the acceptance that will allow for its construction and maintenance.

Step 3: Generate knowledge through academic work by fostering new ideas and approaches in practice and academia and capitalise on the unique and open relationship that students and residents build.

Step 4: Produce hypotheses and guidelines to delineate design work to site-specific aspects of the settlement that need to be considered in the design process.

Step 5: Propose a project that encompasses the whole site to be realised in stages to enable the scale of integration that the situation of the extreme isolation of informal settlements requires.

Step 6: Define a process of construction and maintenance to ensure the commitment of the community towards the construction and maintenance of public space, generating a sense of belonging that can allow for its long-term survival.

Informality as a social form

Coming back to Barber and the omission in his taxonomy chart, with respect to the issue in question here, if we place the ‘informal city’ in the ‘social form’ slot, we propose the following as the missing parameters that can allow for this pervasive urban phenomenon to take its place within the universe of ‘democratic space’:

| Social form | Informal city. |

| Social space | Pathway: connective spaces that appear spontaneously in the process of the formation of a settlement. |

Social buildings | Clubs: spaces for sports and cultural activities that act as the civic catalysts of social ties. |

Governing norm | Inequality: informal settlements’ neighbours do not enjoy the same rights as formal city ones do. |

Human type | Outcast: all civic activities become more complicated for informal settlement inhabitants. |

Social type | Cooperative: neighbour-driven enterprise that propels the organisation of alternative solutions for problems. |

Economic type | Underground/black market: an average of 50% unemployment and endemic poverty rates make business organisation impossible and related taxes unaffordable. |

Written by Caroline Dahl

October 2022

General Credits for photography: Max Rohm, Flavio Janches, Cindy Wouter, Sergio Teubal, Lorena Ramundo, Pablo Gerson, Francisco Berretaga.

Illustration credits: Max Rohm, Flavio Janches

(En svensk version av denna text finns publicerad på SLU Tankesmedjan Moviums webbplats)

References

The project “Urban Interrelations” was instated by Flavio Janches, professor of architecture and urban design, and Max Rohm, both of whom work at the University of Buenos Aires. This was done in collaboration with the inhabitants of Villa Tranquila, the Municipality of Avellaneda, and Harvard GSD students and faculties. The aim of the project was to develop a methodology for the integration of informal settlements into the city through the insertion of public space, which could be used to aid similar efforts in low-income communities around the world. The Vila Tranquila project has become a reference project in the transdisciplinary research of Flavio Janches and Lisa Diedrich, professor of landscape architecture at SLU and director of SLU Urban Futures. They are currently preparing to foster the co-transfer of knowledge between Global South and Global North, in collaboration with researchers and teachers at the Technical University of Berlin, Germany. Lessons learnt from the Global South are meant to inspire a Living Lab supported by Stadtmanufaktur Berlin: https://stadtmanufaktur.info/en/living-labs/generating-common-grounds-on-the-move/

Share

Co-creation!

Do you miss something here? Would you like to contribute? Please let us know: urbanfutures@slu.se