Extreme urban heat – a serious threat in cities and a contemporary health hazard

Published 5 March, 2024

In order to deepen the conversation and to raise awareness of the dangers of increasing urban heat in the realm of urban planning, we met with Mark J Nieuwenhuijsen, Research Professor, Director of the Urban Planning, Environment and Health Initiative, and Head of the Climate, Air Pollution, Nature and Urban Health Programme at IS Global; Anna Mavrogianni, Professor of Sustainable, Healthy and Equitable Built Environment at the University College of London; and Anders Larsson, Researcher and Teacher in Landscape Planning at SLU.

In a nutshell

- As heatwaves become more frequent due to climate change, and as temperatures are rising, raising awareness about the associated health risks is crucial.

- The negative health impacts of heatwaves are preventable through better urban planning, strategically using green and blue spaces.

- Heatwaves can acutely affect large populations quickly, especially older and vulnerable populations, triggering public health emergencies, and affecting the capacity of health services.

- Sprawling development with heavy car use worsens heat islands. Long-term attentive densification planning is needed, focusing on sustainability and thoughtful design.

Urban spaces are facing increased risks due to heatwaves and high temperatures connected to Urban Heat Islands

In the context of climate change, heatwaves are among the most dangerous of natural hazards for public health and city landscapes. The negative public health impacts of heat in cities are to some extent predictable and preventable; there is an awareness of how planning practices can impact the increase and/or reduction of extreme temperatures. Mitigation and prevention interventions can save lives and alleviate the risk factors affecting the health and well-being of all people and ecosystems, which is important for a sustainable and equitable urban development at present and in the future.

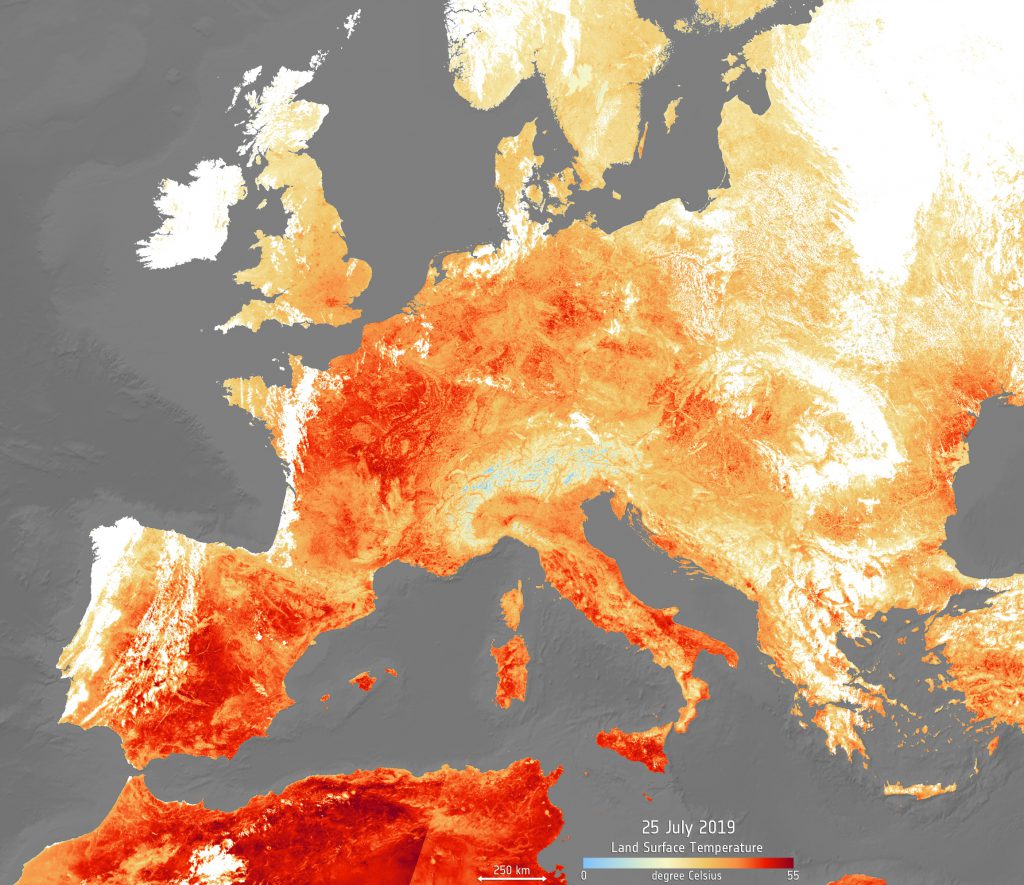

More awareness of the health risks of heat are necessary for prevention

During periods of sustained high temperatures, often during summers, certain areas suffer from an unusual sequence of abnormally hot days and nights. Heatwaves in the last year have broken records of the highest temperatures and will become increasingly common in frequency, according to the IPCC. Cities are usually hotter than rural environments, owing in large part to characteristics of the built environment, such as surface and building material, missing ventilation corridors, the lack of green spaces, and mobility practices that re-emit and produce heat, which create the phenomenon of Urban Heat Islands. Urban Heat Islands and heatwaves are two different phenomena that can have an amplifying effect on urban heat and make city centers susceptible to extreme temperatures with alarming effects on public health, according to WHO.

Exposure to excessive heat and extended exposure to high temperatures is cumulative and has a broad range of physiological and psychological impacts across the population, and is often worse for more physiologically vulnerable individuals. These include higher risks for elderly, children, pregnant women, individuals with underlying conditions, outdoor workers, athletes exercising outdoors and socio-economically vulnerable groups. Physiological risks include dehydration, respiratory difficulties, heat strokes, cardiovascular and kidney complications, and an increase in heat premature mortality. Heatwaves can acutely affect large populations quickly, triggering public health emergencies, and affecting the capacity of health services. In 2022, around 61,000 people in Europe died as a consequence of the heatwaves, with 700 deaths in Sweden. Whilst the impact of heat on humans was presented as a core research focus at a Conference at UCL in Neurology last year, more work needs to be done to further develop research capacities and to communicate research to the public and public health officials. Research so far has shown that both short-term and long exposure to heatwaves can impair many of our cognitive functions, such as reduced attention and ability to focus, impaired memory consolidation and learning, reduced decision and problem-solving abilities, and slowing reaction times. However, these health threats connected to heatwaves need to receive more coverage in the public health debate.

A warmer climate also affects ecological cycles and the seasonal timing of the biological events of fauna and flora in cities. For example, heatwaves quickly degrade the water quality of rivers and water sources, which has impacts on the ecosystem and water systems – including the quality of potable water. Another example, highlighted in a recent study, found that bumblebees wake from hibernation too early, which affects their ability to find food sources and ultimately causes their death. The consequences of such ecological changes are causing the rapid loss of pollinating animal species and consequently the loss of plant and animal species that underpin life.

Awareness about the health risks of increased temperatures remains insufficient. Professor Anna Mavrogianni explains that the problem relates to how history has changed and how new the problem is:

“Some climate change risks are more easily understood because they are visible, for example, floods. Besides, heat and heatwaves are sometimes presented in the media in a very positive way, as, for example, ’the barbecue weather’. Furthermore, in countries in Northern Europe and America, the focus has historically been on retaining heat rather than getting rid of it. This creates a challenge in the communication of the risks of heatwaves and in the inclusion of the topic in the planning and research agenda. A potential barrier is that many people do not perceive heat as dangerous and harmful for them, and research shows that individuals most at risk do not perceive themselves as being at risk. Therefore, there is a need for a culture shift in heat risk communication and management”.

Understanding the complexities for planning and the equality dimensions of urban heat islands are central for effective mitigation and prevention

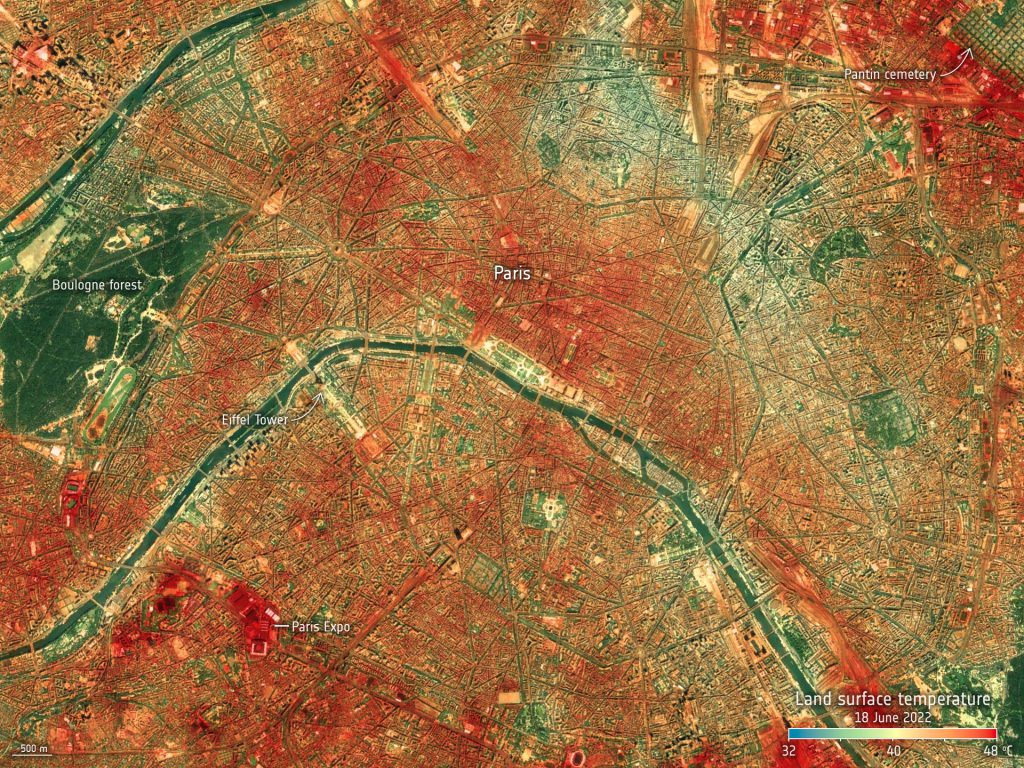

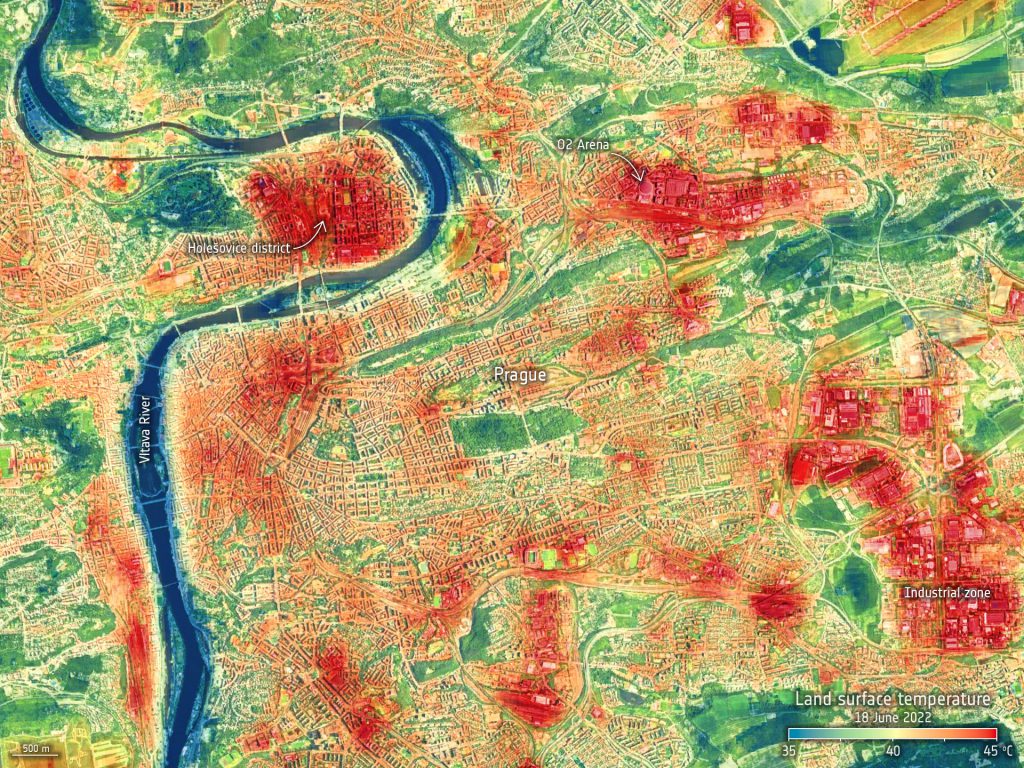

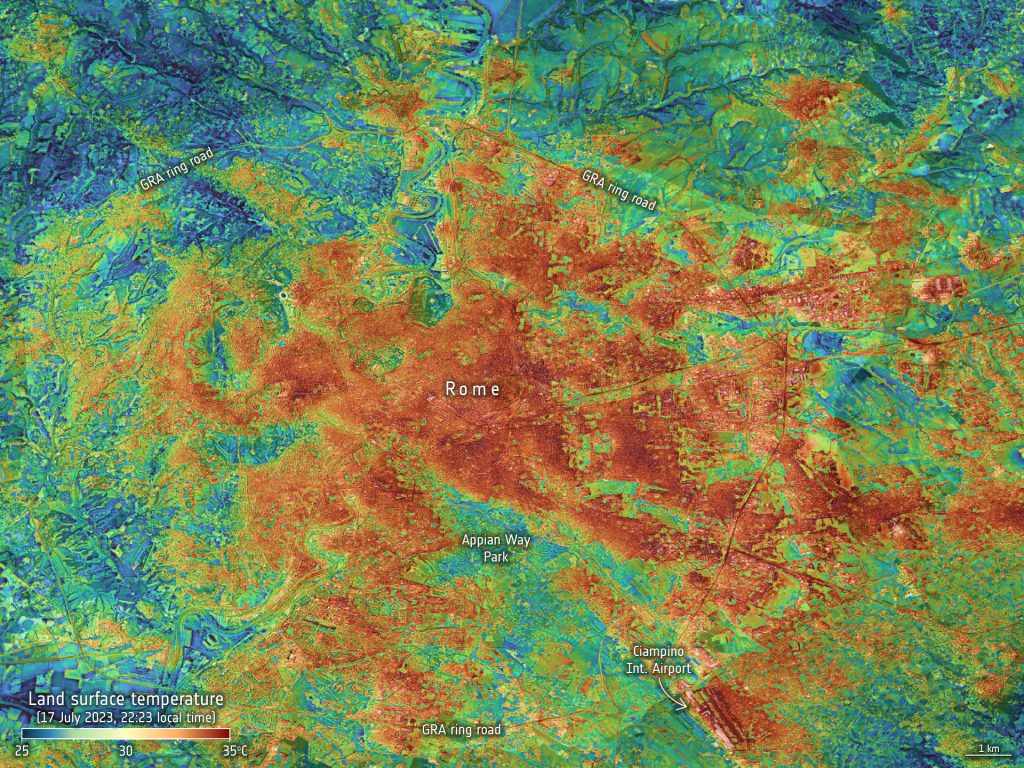

The phenomenon of Urban Heat Islands occurs when vast, dense urban infrastructures, such as buildings and the impermeable surfaces of asphalt and concrete, and transportation systems, absorb and re-emit heat. A further amplifying factor is a lack of properly planned green environments, which mitigate heat in urban environments. This leads to significantly higher temperatures in cities compared to surrounding rural areas, forests and water bodies. Planning differences cause temperature variations even in-between spaces in the same city and differences relating to equality. In the global north, is a pattern of socio-economically vulnerable communities living in the hottest areas. In particular green space is not equally distributed across cities, and, in a European context, poorer neighboorhoods tend to have less green spaces than richer neighbourhoods. These differences in accessibility affect some population groups more than others and become an issue of equity, as poorer groups are more exposed to health threats.

A satellite map shows the ground temperatures in Paris, France, on 18 June 2022, during one of the record-breaking heatwaves. The hottest surfaces, which are sealed surfaces in the built environments, can be clearly identified in red. The absence of red around parks, forest areas, green spaces and water demonstrate their cooling effects. Copyright: NASA/JPL-Caltech

A classic phenomenological book Heat Wave, by Klinenberg, published in 2002, explored the 1995 heat wave in Chicago, in a method that went beyond the traditional analysis of medical causes of death. The study used intensive fieldwork, public documents, and in-depth interviews with residents and urban planners of two adjacent neighborhoods. The study demonstrated how spatial, material and social equality differences played a central role in people´s behaviors, contributing to dramatically different heat-wave mortalities. Klinenberg argued that social realities, such as poverty and isolation, create differences between places and human sociability, which makes some groups more vulnerable. Isolation of individuals, social differences in behavior, inadequate buildings and reduced social services, were found to be obstacles to people seeking help during these periods. A central conclusion is that social differences and practices need to be understood in order to address the differences in vulnerabilities in the city and therefore to make health interventions more effective.

More collaboration across scales and professions is needed to cool down cities

During these periods of heat, during day and night, air circulation becomes more than just a comfort, but a necessity. The built environment needs to allow for overall cooling processes, which represents an urban planning challenge. Moving natural air is important to cool down outdoor environments and indoor environments in homes. Fresh air circulation can replace stagnant, hot air, reducing humidity and preventing overly hot temperatures. The density, size and positions of buildings without green environments may impede wind flow and can create pockets of stagnant air. Planning and architectural practices that integrate natural ventilation can optimize airflow, which affects the temperatures of outdoor and indoor environments. Furthermore, good outdoor ventilation can reduce the need for energy-intensive devices that overload energy systems. Artificial indoor ventilation systems such as air conditioners tend to be energy and resource-intensive and typically rely on fossil fuels, creating more carbon emissions. Further collaboration between professions is required to create and implement designs to cool down our cities (both outdoors and indoors) whilst simultaneously saving resources and reducing emissions.

Professor Anna Mavrogianni explains that this is a complex issue that relates to interconnected challenges in planning:

“Allowing for natural ventilation in buildings can be quite tricky in some settings, because there are areas characterised by high ambient and noise pollution, and people might not be willing to open their windows due to these or other concerns, such as safety or security risks.”

Professor Mark J. Nieuwenhuijsen explains that the development of new urban models can help mitigate, prevent and reduce health burdens, whilst being more conscious of the needs and risks of different populations. The EU-funded Urban Burden of disease estimation for policy making project (UBD Policy project) looks at the impact of air pollution, built environments, noise, heat, and lack of green space on the health of people across 1000 cities in Europe. He explains:

“There are a lot of policies that drive us to a car-centric way of living which stimulates our car dependency. To a large extent, many problems in city planning that cause the heat effects, and the issues of air and noise pollution, come from motorized traffic. It is important that city councils looks at the development of more complex cities, in terms of the needs of transportation, and the needs of people and their well-being, which includes also the need for more green space. There is a central problem of long distances between the places where people live and their jobs, which leads to people having to travel a long time on an everyday basis.”

Professor Mark J Nieuwenhuijsen gives some examples of good planning practices that can provide traffic-calming effects by reducing the quantities of cars through the development of new street hierarchies that prioritize walking and biking:

“In terms of transportation, the 15-minute city from Carlos Moreno, is a good model. Or, for example, in London, the ultra-low traffic neighborhoods, reduce traffic in certain areas. Another example is the Barcelona Superblock, a grid system for streets going up and down, left and right – the idea is to cut off four junctions and then put in more green space and allow pedestrians and cyclists to take place. In our research projects at IS Global, we have found that in Barcelona, there is a big difference in temperature in streets with trees and with no trees. It can be easily 5-10 degrees cooler in streets with trees.”

Photo: Nick Wehrli, Pexels

Professor Anna Mavrogianni further explains that densely-built areas are central to the phenomenon of heat islands. The materials used in building structures are important. She explains:

“Heat is absorbed by the building structures, and the rate of heat dissipation depends on the physical characteristics of these materials. It is important to think about the sustainability aspects of the materials we use in cities, in particular their thermal performance under a changing climate. The introduction of high reflectivity materials and shading are important heatwave mitigation strategies in urban areas.”

Researcher Anders Larsson has studied urban growth from a landscape planning and landscape quality perspective. He explains that urban planning is a complex profession that affects both land-use and transport planning. Cities should be densified responsibly in order to simultaneously and effectively use the existing built environment while creating more and better green environments. He argues that unplanned sprawling, that is, the unrestricted spreading of urban environments with roads and large use of land, is a problematic way to develop cities because it creates an overuse of asphalt and other impermeable surfaces, which increases the risk of Urban Heat Islands.

“If we continue this trend, we would double the amount of built-up area in 20 years, which would have tremendous negative effects”, he explains.

“The way we plan and build up our systems is extremely important. Historically, many cities in Sweden have expanded tenfold during approximately a hundred years. Sweden has an extremely scattered landscape, where cities have a lot of roads, and there is a lot of asphalt, one of the highest road surface areas per capita in the world. It becomes a lot of asphalted areas that in many cases could be devoted to creating green spaces instead”

“Planning traditions and practices are very difficult to change, and already sprawled cities are difficult to densify in a smart way. Hong Kong, for example, accommodates approx. 7.3 million inhabitants in the same area as Hässleholm municipality, in Skåne, Sweden. Hässleholm municipality has approx.. 52000 inhabitants. There is a difference between how much area and which areas these two cities use for further growth and development.”

He explains that newly built environments in this context, have repeatedly used sites on fertile land instead of using already built-up areas, which can be criticized from a sustainable land-use perspective.

“Another example is Atlanta in the USA compared with Barcelona. Both cities have approximately the same number of inhabitants, while Barcelona is almost ten times more dense and Atlanta is spread out over much wider territories. Barcelona has more preserved land outside the urban area, more apartment buildings and quite few skyscrapers, while Atlanta has many more private villas with big gardens and quite many skyscrapers in the central parts of the city. It is of course hard to compare two such very different structures, but the total amount of artificial surfaces is much higher in Atlanta, which will be negative regarding the amount of extreme heat events.”

A long-term planning process for resilient urban landscapes

Cities are dynamic and ever-evolving, housing complex relationships between human needs and wants and ecosystem dynamics. Heatwaves affect both the current landscape and future generations and development. That is why a more complex, well-thought-out, and long-term planning perspective is vital for shaping sustainable urban landscapes. A focus on mitigation and prevention in different planning processes should be even more incorporated into regulations, to minimize various risks. Professor Anna Mavrogianni explains how to comply with measures to reduce the health risks for people during heatwaves in city planning:

“There is a firefighting element, a focus on the response during a crisis, such as an extreme weather event. A heat alert system and an emergency response are very important, and cities need to develop these with an awareness of the impact of heatwaves. However, the focus should be on prevention, long before the events. In order to have heat resilient planning and buildings, green spaces and have fewer people at risk, then you should think about your building regulations and the kind of cooling measures that are integrated in your design.”

Landscape design needs to shape places that prioritise heat-related safety and comfort, especially for vulnerable groups like the elderly and children. Schoolyards, parks, and beaches –popular spaces during summer – demand a conscious shift towards elements that help cool down spaces. The importance of shade, ventilation, and type of suitable vegetation for extreme heat, are complex design aspects that should be integrated in the planning of green environments for the future.

Professor Anna Mavrogianni explains:

“We need to avoid simplistic associations such as “green will reduce heat risk” without the consideration of very complex factors in place, such as, in the case of an urban park, the presence of shading and seating areas and overall welcoming nature of a public space. It is important to create heat-resilient urban spaces in a way that they meet the needs of the citizens.”

Professor Mark N. Nieuwenhuijsen explains the need to genuinely engage with the long-term, multivalent and complex task of urban green space development as one of the most crucial foci for the sustainable development of cities. He says: “City councils should aim to develop their green spaces, and there is a need to have a long-term program in place for greening. It takes a long time to grow trees and the cooling effect depends very much on how many trees there are and how much vegetation there is. The trees provide quite a lot of cooling and other advantages but there is a need for a very good strategy and good plans for where to put the trees to make it work. A planted tree today will not give benefits in the next year, but these trees are growing and you will get the main benefits from cooling but also from the carbon sequestration. Furthermore, research shows that many planted trees die within about two years due to a lack of management. The drought that happens during heatwaves often makes the situation worse. For example, in Barcelona, when we had a drought last year, trees could not be watered and new trees could not be planted, which is a problem. You need to be attentive to pollen as well, to not cause allergies.”

Long-term planning is not a single formula for all cities, but a complex process that requires continuous adaptation and mitigation. An understanding of the local particularities and needs and an awareness of the challenges of different spaces as well as long-term prospects are key. In this article, we have deepened the discussion around some aspects of urban development and planning that are problematic and produce heat island effects. The use of materials for surface structures and buildings can increase or retain heat. The wind and air circulation in the city through large structures (corridors, parks, open areas) is necessary, and it is also affected by the buildings’ size and position. Green and blue structures are important to cool down cities, but they need to be integrated in ways that cool cities effectively. Shadow and trees are important to offer refuge and cooler areas, also decreasing the overall temperatures at a macro level. Car-dependent and sprawled environments are related to higher risks for Urban Heat Islands and should be avoided. Sprawled development impacts mobility behavior and thus transport infrastructures, resources and material use; instead, a densified development that incorporates elements of the built environment to cool and mitigate heat is a more desirable planning approach in the long term.

A landscape planning perspective on urban development can offer sustainable alternatives for the built environment that can mitigate, prevent, and protect people from the risks of heatwaves, related not only to comfort but to serious health hazards. SLU Urban Futures aims to gather global experts’ and SLU’s expertise to lift integrated landscape planning approaches that can support desirable urban development for humans, animals and ecosystems and the design of liveable urban spaces of the future.

Written by Amanda Gabriel

March 2024

Read more about this article series here.

Read more

Cooling cities through urban green infrastructure: a health impact assessment of European cities

About differences and problems in Urban Planning, discussing sprawling: Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities – Alain Bertaud

Staying safe during a heatwave, Unicef

Share

Co-creation!

Do you miss something here? Would you like to contribute? Please let us know: urbanfutures@slu.se