The Campus as a Living Lab – How Utrecht University is co-producing targeted sustainability solutions

Published 9 March, 2022

Society faces a multitude of complex sustainability challenges, which require new ways of thinking and doing. Universities, with their assets and knowledge, play an influential role in facilitating such change by collaborating across disciplines and sectors. Using their space and resources, universities are increasingly bringing together new constellations of actors on-site to explore and develop new methodologies to address societal challenges. In other words, using the campus as a living lab, to “design, test and learn from innovation in real-time.” (Menny et al., 2018). A living lab methodology is being tried and tested by a team at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, producing some interesting results.

The Green Office Living Lab at Utrecht University has been running for seven years, with the goal to connect students to real-world sustainability challenges, happening at the campus. The main idea is to engage students and operational staff members to solve challenges that the university is facing, in-house, and at the same time provide students with research experience, while being supervised by an expert. Tom McDevitt is the living lab coordinator at the Utrecht Green Office.

“My role is to collect questions, relating to sustainable campus development, from operation staff members at the campus. The questions are then taken to researchers to see if they are relevant as a part of their courses or as a thesis question.”

After a few years in operation, the Green Office team encountered a problem with the model they were working with.

“The projects at the Green Office Living Lab are often limited to 10 weeks. We felt that was a bit short,” Tom explains. “The questions are often really complex, and having students working on them for such a short period, while also taking other courses, was often too much to handle.”

As the team kept learning more about living lab methodology, via literature and other case studies, they realized that their projects were not always ‘true living labs’.

“The projects we had were not really bringing together stakeholders from different backgrounds or different expertise to work on one single problem. So we decided to expand the Green Office Living Lab concept.”

In order to truly work in living lab constellations, the team needed to increase the engagement of the researchers and operational staff, and ask them to bring their own networks and expertise to the table. A new model had to be created and this is where the UU Labs was born.

Universities have unique opportunities to incorporate the living lab methodology and include diverse stakeholders to co-create solutions for future challenges.

The Utrecht University Living Labs for Sustainable Development

Influenced by Prof. Dr John Robinson and his work on the Campus as a Living Lab in Canada, the team was inspired to apply this methodology at their campus. Looking at a campus as a miniature city – with education, businesses, housing, shopping and public transport infrastructure all at the neighborhood scale – it provides an ideal landscape for testing, experimenting and developing a wide range of solutions to societal challenges, ready to be scaled up.

An important starting point for the Living Labs at Utrecht Campus was the creation of a new Strategic Plan for the university. The governing document for 2020-2025 includes the living lab methodology in one of the main strategic action points (here translated to English):

“We create testing grounds for sustainability in our buildings and on our [campus] grounds, in which we bring together education, research and business operations”

This inclusion strengthened the motives and offered a mandate for working with Campus as a Living Lab, and the Green Office Living Lab became a part of the bigger umbrella: The UU Labs. Mark Kauw became the project manager.

“The reason that I decided to start working for the university was the opportunity of collaboration between science and operations. I wanted to see interesting experiments, involving students, targeting sustainability challenges,” says Mark.

Universities have unique opportunities to incorporate the living lab methodology and include diverse stakeholders to co-create solutions for future challenges. A campus area is a relatively controlled environment with fewer uncertainties, compared to other urban neighborhoods. This affects the way living labs can be managed and developed.

“Universities have an influential role in society. They are excluded from traditional business and political cycles, are globally considered as trustworthy institutions, and often expected to lead the way,” says Mark.

How to find each other within the university – across faculties – remains a big challenge.

Building a network

The team at the UU Labs started to contact other universities to find out what they were doing, and to gather evidence to convince the Utrecht university management that investment was needed in order to truly work with living labs on the campus – on a long-term basis.

“We came in contact with Nina Vogel at SLU in Alnarp, among others, and a network was formed that exchanges knowledge and experiences at workshops four times a year,” Mark explains.

The team also reached out to operational staff and researchers throughout Utrecht University to gather their thoughts on this methodology. Would living labs be useful in their projects? Would they be useful for their students? Which networks could they bring in?

“The feedback was overwhelmingly positive,” says Tom McDevitt. “Many were really interested in the idea but they were hesitant to commit because they simply didn’t have time.”

The three main obstacles they came across in their talks were related to resources and management: time, money and coordination.

“How to find each other within the university – across faculties – remains a big challenge,” says Mark.

Managing new methods of working

The core team of the UU Labs today consists of 14 people, both researchers and operational staff members, setting aside one or two hours per week to work on living labs.

“Our day-to-day job is actually getting people together, getting them around a table, explains Tom McDevitt. The next step is making sure there is seed-funding that will compensate the hours for the persons working with the projects.”

The team has a good overview of research and activities taking place at the university. They know who is who at the faculties and also what is going on at the operations level. This means that the team can build cross-disciplinary collaborations that can add value to a project.

“Managing new methods of working is challenging, especially when people are constrained with busy schedules and traditional targets and deadlines set on them. The UU Labs team is needed to facilitate the work in living labs at campus,” says Mark.

The various labs are categorized into four key themes at the UU Labs: climate action, circularity, biodiversity and a fourth more open-ended one called creative space. These categories help to tie the labs to different Sustainable Development Goals, but also to identify what the networks and connections look like.

Next to matchmaking, the UU Labs manages logistics, timing and funding when necessary, as well as conducting evaluations and facilitating further opportunities for collaboration to drive the projects forward.

“We work behind the scenes connecting, organising and facilitating the space and opportunity for these collaboration and co-production forms,” says Mark.

A sheep meadow at the campus ground

A campus area can become a breeding ground for exploring new practices and learning models. In a living lab people from public and private sectors, from academy as well as civil society can meet and form new innovation networks.

“You might think we are in a completely urban area here, but there is a sheep meadow just 200 meters that way, ” Mark says pointing out the window.

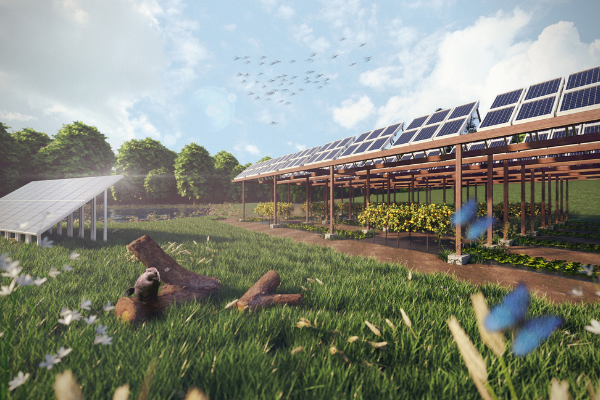

The meadow, where sheep from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine are grazing, is one of the current living labs at the Utrecht campus. The project includes aspects of biodiversity, cultural heritage and renewable energy; and involves external partners such as the municipality and a solar panel company.

“The main goal of this lab is to help the university integrate solutions to achieve some of its top climate goals: energy neutrality and enhancing and restoring biodiversity,” says Mark.

Using the meadow as a test case to diversify land-use practices – i.e. grazing of sheep and photovoltaics (PV) energy generation, while also providing a space for experimentation, will in the long-term provide solutions to wider societal problems.

Students and researchers will be working together with operational staff to test how PV panels impact sheep grazing, how to enhance biodiversity around these solar panels and ensure efficient land-use, as well as research into the PV panels and battery technology themselves. The living lab also includes sociological research into aesthetics and ‘not in my backyard’ challenges. This study will help to address the challenges of implementing renewable energy solutions necessary for the energy transition.

Ethical aspects of living labs

In the spring of 2022, David V Spiegelman, an international master’s student is joining the UU Labs to look at the ethical aspects of working with living labs. David is working toward a master of applied ethics and will apply his knowledge on existing and potential living labs at Utrecht campus.

“I am going to look at possible conflicts of interests and identify ethical problems and tensions that might arise. Preferably before they arise,” David explains. “The sheep meadow is one example, where some people who are working around that field are unhappy with the green field turning into solar panels.”

The UU Labs are also looking at setting up a living lab that will be monitoring the central campus, using sensors and cameras, monitoring the movement of people.

“That kind of lab would generate many questions and concerns regarding privacy, data collection and explicit consent.”

The proposal to build a wind turbine on campus, is another example of a lab that requires an ethical assessment. In the area suggested to construct the turbine, there is a worry that such a project would cause serious harm to biodiversity. The goal of increasing green energy is therefore in direct conflict with the preservation of biodiversity, and an ethical assessment will help determine what the best course of action would be.

A sense of community

At the moment, many academics are enthusiastic and willing to engage in these meaningful labs in Utrecht, but currently their work and extra hours would end up un-compensated. Mark Kauw believes that helping to ease the work burden and ensuring that their time is compensated properly, will positively affect the quality of the labs.

He also emphasizes the importance of ensuring a sense of community, not only for the success of the projects but also for the well-being and sense of purpose of the participants in the lab.

“Working to maintain the network, keep people informed, and organize events, where people can meet in real life, are key parts of our vision. The real-life chats, discussions and brainstorms are important,” emphasizes Mark.

Tom adds that the network has grown to more than 100 people and, like most other networks in the last couple of years, they have only been able to meet online.

“An important component in living labs is co-creation – people with different backgrounds, sharing ideas and together you formulate an answer. Doing that online in break-out rooms is simply not the same,” says Tom.

The team is looking forward to seeing the living labs develop at a higher speed when the restrictions from the Covid-19 pandemic are lifted. Meetings and co-production on-site is clearly a prerequisite for living labs to live and thrive.

“We also hope to engage more with SLU in the future and are curious to hear more about the Campus PhD project in Alnarp,” says Mark. “Collecting stories of inspiring labs helps to get people on board and build the living lab community!”

Written by Hanna Weiber-Post

SLU Urban Futures

March 2022

Living Labs

Living Labs are “user-centered, open innovation ecosystems based on systematic user co-creation approach, integrating research and innovation processes in real life communities and settings”. – The European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL)

Utrecht University Living Labs

The University Campus as a Living Lab for Sustainability – A Practitioner’s Guide and Handbook (Leendert Verhoef and Michael Bossert, 2019)

Jointly Experimenting for Transformation? Shaping Real-World Laboratories by Comparing Them (Schäpke, N. et al.,2018)

Urban Living Labs and the Role of Users in Co-Creation (Menny et al., 2018)

Urban living labs: governing urban sustainability transitions (Bulkeley, et al.,2016)

Share

Co-creation!

Do you miss something here? Would you like to contribute? Please let us know: urbanfutures@slu.se